- Home

Page 11

Page 11

The Lost World

The Lost World A Study in Scarlet

A Study in Scarlet The Firm of Girdlestone

The Firm of Girdlestone The Cabman's Story

The Cabman's Story The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Round the Fire Stories

Round the Fire Stories His Last Bow: An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes

His Last Bow: An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes Micah Clarke

Micah Clarke The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard

The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard The Gully of Bluemansdyke, and Other stories

The Gully of Bluemansdyke, and Other stories The Valley of Fear

The Valley of Fear The Last of the Legions and Other Tales of Long Ago

The Last of the Legions and Other Tales of Long Ago The Dealings of Captain Sharkey, and Other Tales of Pirates

The Dealings of Captain Sharkey, and Other Tales of Pirates The Hound of the Baskervilles

The Hound of the Baskervilles The Great Shadow and Other Napoleonic Tales

The Great Shadow and Other Napoleonic Tales The Adventure of the Dying Detective

The Adventure of the Dying Detective The Man from Archangel, and Other Tales of Adventure

The Man from Archangel, and Other Tales of Adventure The Poison Belt

The Poison Belt The Last Galley; Impressions and Tales

The Last Galley; Impressions and Tales The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge

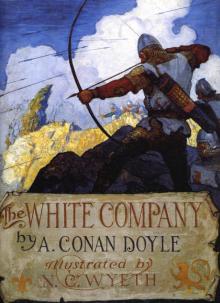

The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge The White Company

The White Company The Mystery of Cloomber

The Mystery of Cloomber The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans

The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans The Adventure of the Cardboard Box

The Adventure of the Cardboard Box Danger! and Other Stories

Danger! and Other Stories Sir Nigel

Sir Nigel The Return of Sherlock Holmes

The Return of Sherlock Holmes The Adventure of the Devil's Foot

The Adventure of the Devil's Foot The Adventure of the Red Circle

The Adventure of the Red Circle The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes The Adventure of the Yellow Face

The Adventure of the Yellow Face The Adventure of the Norwood Builder

The Adventure of the Norwood Builder Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes

Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter

The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter The Adventure of the Final Problem

The Adventure of the Final Problem A Scandal in Bohemia

A Scandal in Bohemia His Last Bow shssc-4

His Last Bow shssc-4 Beyond The City

Beyond The City The Adventure of the Gloria Scott

The Adventure of the Gloria Scott The Parasite

The Parasite The Land Of Mist pcs-3

The Land Of Mist pcs-3 The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual

The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk

The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk The Adventure of the Copper Beeches

The Adventure of the Copper Beeches The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes When The World Screamed pcs-5

When The World Screamed pcs-5 The Adventure of the Six Napoleons

The Adventure of the Six Napoleons The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes shssc-5

The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes shssc-5 The Sign of Four

The Sign of Four Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #10

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #10 The Adventures of Brigadier Gerard

The Adventures of Brigadier Gerard The Adventure of the Second Stain

The Adventure of the Second Stain The Adventure of the Engineer's Thumb

The Adventure of the Engineer's Thumb The Mummy Megapack

The Mummy Megapack The Disintegration Machine pcs-4

The Disintegration Machine pcs-4 The Maracot Deep

The Maracot Deep The Five Orange Pips

The Five Orange Pips The Adventure of the Crooked Man

The Adventure of the Crooked Man The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle

The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle The Adventure of Silver Blaze

The Adventure of Silver Blaze The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist

The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist The Adventure of the Naval Treaty

The Adventure of the Naval Treaty Sherlock Holmes. The Complete Stories

Sherlock Holmes. The Complete Stories The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (sherlock holmes)

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (sherlock holmes) The Adventure of the Empty House

The Adventure of the Empty House The Narrative of John Smith

The Narrative of John Smith The Return of Sherlock Holmes (sherlock holmes)

The Return of Sherlock Holmes (sherlock holmes) The New Revelation

The New Revelation A Study in Scarlet (sherlock holmes)

A Study in Scarlet (sherlock holmes) The Vital Message

The Vital Message Sherlock Holmes Complete Collection

Sherlock Holmes Complete Collection Round the Red Lamp

Round the Red Lamp The Boscombe Valley Mystery

The Boscombe Valley Mystery The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet

The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet The Refugees

The Refugees The Adventure of the Three Students.

The Adventure of the Three Students.